19.08.14: 2000th anniversary of the death of Octavian Augustus, first Prince of the Roman Empire (63 BC – 14 AD).

“Survey,” pursued the sire, “this airy throng,

As, offer’d to thy view, they pass along.

These are th’ Italian names, which fate will join

With ours, and graff upon the Trojan line.

Observe the youth who first appears in sight,

And holds the nearest station to the light,

Already seems to snuff the vital air,

And leans just forward, on a shining spear:

Silvius is he, thy last-begotten race,

But first in order sent, to fill thy place;

An Alban name, but mix’d with Dardan blood,

Born in the covert of a shady wood:

Him fair Lavinia, thy surviving wife,

Shall breed in groves, to lead a solitary life.

In Alba he shall fix his royal seat,

And, born a king, a race of kings beget.

Then Procas, honor of the Trojan name,

Capys, and Numitor, of endless fame.

A second Silvius after these appears;

Silvius Aeneas, for thy name he bears;

For arms and justice equally renown’d,

Who, late restor’d, in Alba shall be crown’d.

How great they look! how vig’rously they wield

Their weighty lances, and sustain the shield!

But they, who crown’d with oaken wreaths appear,

Shall Gabian walls and strong Fidena rear;

Nomentum, Bola, with Pometia, found;

And raise Collatian tow’rs on rocky ground.

All these shall then be towns of mighty fame,

Tho’ now they lie obscure, and lands without a name.

See Romulus the great, born to restore

The crown that once his injur’d grandsire wore.

This prince a priestess of your blood shall bear,

And like his sire in arms he shall appear.

Two rising crests, his royal head adorn;

Born from a god, himself to godhead born:

His sire already signs him for the skies,

And marks the seat amidst the deities.

Auspicious chief! thy race, in times to come,

Shall spread the conquests of imperial Rome

Rome, whose ascending tow’rs shall heav’n invade,

Involving earth and ocean in her shade;

High as the Mother of the Gods in place,

And proud, like her, of an immortal race.

Then, when in pomp she makes the Phrygian round,

With golden turrets on her temples crown’d;

A hundred gods her sweeping train supply;

Her offspring all, and all command the sky.

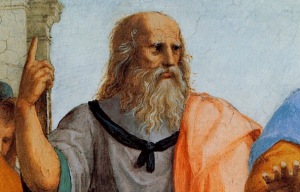

“Now fix your sight, and stand intent, to see

Your Roman race, and Julian progeny.

The mighty Caesar waits his vital hour,

Impatient for the world, and grasps his promis’d pow’r.

But next behold the youth of form divine,

Ceasar himself, exalted in his line;

Augustus, promis’d oft, and long foretold,

Sent to the realm that Saturn rul’d of old;

Born to restore a better age of gold.

Afric and India shall his pow’r obey;

He shall extend his propagated sway

Beyond the solar year, without the starry way,

Where Atlas turns the rolling heav’ns around,

And his broad shoulders with their lights are crown’d.

At his foreseen approach, already quake

The Caspian kingdoms and Maeotian lake:

Their seers behold the tempest from afar,

And threat’ning oracles denounce the war.

Nile hears him knocking at his sev’nfold gates,

And seeks his hidden spring, and fears his nephew’s fates.

Nor Hercules more lands or labors knew,

Not tho’ the brazen-footed hind he slew,

Freed Erymanthus from the foaming boar,

And dipp’d his arrows in Lernaean gore;

Nor Bacchus, turning from his Indian war,

By tigers drawn triumphant in his car,

From Nisus’ top descending on the plains,

With curling vines around his purple reins.

And doubt we yet thro’ dangers to pursue

The paths of honor, and a crown in view?

But what’s the man, who from afar appears?

His head with olive crown’d, his hand a censer bears,

His hoary beard and holy vestments bring

His lost idea back: I know the Roman king.

He shall to peaceful Rome new laws ordain,

Call’d from his mean abode a scepter to sustain.

Him Tullus next in dignity succeeds,

An active prince, and prone to martial deeds.

He shall his troops for fighting fields prepare,

Disus’d to toils, and triumphs of the war.

By dint of sword his crown he shall increase,

And scour his armor from the rust of peace.

Whom Ancus follows, with a fawning air,

But vain within, and proudly popular.

Next view the Tarquin kings, th’ avenging sword

Of Brutus, justly drawn, and Rome restor’d.

He first renews the rods and ax severe,

And gives the consuls royal robes to wear.

His sons, who seek the tyrant to sustain,

And long for arbitrary lords again,

With ignominy scourg’d, in open sight,

He dooms to death deserv’d, asserting public right.

Unhappy man, to break the pious laws

Of nature, pleading in his children’s cause!

Howeer the doubtful fact is understood,

‘T is love of honor, and his country’s good:

The consul, not the father, sheds the blood.

Behold Torquatus the same track pursue;

And, next, the two devoted Decii view:

The Drusian line, Camillus loaded home

With standards well redeem’d, and foreign foes o’ercome

The pair you see in equal armor shine,

Now, friends below, in close embraces join;

But, when they leave the shady realms of night,

And, cloth’d in bodies, breathe your upper light,

With mortal hate each other shall pursue:

What wars, what wounds, what slaughter shall ensue!

From Alpine heights the father first descends;

His daughter’s husband in the plain attends:

His daughter’s husband arms his eastern friends.

Embrace again, my sons, be foes no more;

Nor stain your country with her children’s gore!

And thou, the first, lay down thy lawless claim,

Thou, of my blood, who bearist the Julian name!

Another comes, who shall in triumph ride,

And to the Capitol his chariot guide,

From conquer’d Corinth, rich with Grecian spoils.

And yet another, fam’d for warlike toils,

On Argos shall impose the Roman laws,

And on the Greeks revenge the Trojan cause;

Shall drag in chains their Achillean race;

Shall vindicate his ancestors’ disgrace,

And Pallas, for her violated place.

Great Cato there, for gravity renown’d,

And conqu’ring Cossus goes with laurels crown’d.

Who can omit the Gracchi? who declare

The Scipios’ worth, those thunderbolts of war,

The double bane of Carthage? Who can see

Without esteem for virtuous poverty,

Severe Fabricius, or can cease T’ admire

The plowman consul in his coarse attire?

Tir’d as I am, my praise the Fabii claim;

And thou, great hero, greatest of thy name,

Ordain’d in war to save the sinking state,

And, by delays, to put a stop to fate!

Let others better mold the running mass

Of metals, and inform the breathing brass,

And soften into flesh a marble face;

Plead better at the bar; describe the skies,

And when the stars descend, and when they rise.

But, Rome, ‘t is thine alone, with awful sway,

To rule mankind, and make the world obey,

Disposing peace and war by thy own majestic way;

To tame the proud, the fetter’d slave to free:

These are imperial arts, and worthy thee.”

—Publius Vergilius Maro, Aeneid (VIII, 756-853)