“And now,” said I, “the fairest polity and the fairest man remain for us to describe, the tyranny and the tyrant.”

“Certainly,” he said.

“Come then, tell me, dear friend, how tyranny arises. That it is an outgrowth of democracy is fairly plain.”

“Yes, plain.”

“Is it, then, in a sense, in the same way in which democracy arises out of oligarchy that tyranny arises from democracy?”

[562b] “How is that?”

“The good that they proposed to themselves and that was the cause of the establishment of oligarchy—it was wealth, was it not?”

“Yes.”

“Well, then, the insatiate lust for wealth and the neglect of everything else for the sake of money-making was the cause of its undoing.”

“True,” he said.

“And is not the avidity of democracy for that which is its definition and criterion of good the thing which dissolves it too?”

“What do you say its criterion to be?”

“Liberty,” I replied; “for you may hear it said that this is best managed in a democratic city, [562c] and for this reason that is the only city in which a man of free spirit will care to live.”

“Why, yes,” he replied, “you hear that saying everywhere.”

“Then, as I was about to observe, is it not the excess and greed of this and the neglect of all other things that revolutionizes this constitution too and prepares the way for the necessity of a dictatorship?”

“How?” he said. “Why, when a democratic city athirst for liberty gets bad cupbearers [562d] for its leaders and is intoxicated by drinking too deep of that unmixed wine, and then, if its so-called governors are not extremely mild and gentle with it and do not dispense the liberty unstintedly, it chastises them and accuses them of being accursed oligarchs.”

“Yes, that is what they do,” he replied.

“But those who obey the rulers,” I said, “it reviles as willing slaves and men of naught, but it commends and honors in public and private rulers who resemble subjects and subjects who are like rulers. [562e] Is it not inevitable that in such a state the spirit of liberty should go to all lengths?”

“Of course.”

“And this anarchical temper,” said I, “my friend, must penetrate into private homes and finally enter into the very animals.”

“Just what do we mean by that?” he said.

“Why,” I said, “the father habitually tries to resemble the child and is afraid of his sons, and the son likens himself to the father and feels no awe or fear of his parents, [563a] so that he may be forsooth a free man. And the resident alien feels himself equal to the citizen and the citizen to him, and the foreigner likewise.”

“Yes, these things do happen,” he said.

“They do,” said I, “and such other trifles as these. The teacher in such case fears and fawns upon the pupils, and the pupils pay no heed to the teacher or to their overseers either. And in general the young ape their elders and vie with them in speech and action, while the old, accommodating themselves to the young, [563b] are full of pleasantry and graciousness, imitating the young for fear they may be thought disagreeable and authoritative.”

“By all means,” he said.

“And the climax of popular liberty, my friend,” I said, “is attained in such a city when the purchased slaves, male and female, are no less free than the owners who paid for them. And I almost forgot to mention the spirit of freedom and equal rights in the relation of men to women and women to men.”

[563c] “Shall we not, then,” said he, “in Aeschylean phrase, say “whatever rises to our lips’?”

“Certainly,” I said, “so I will. Without experience of it no one would believe how much freer the very beasts subject to men are in such a city than elsewhere. The dogs literally verify the adage and ‘like their mistresses become.’ And likewise the horses and asses are wont to hold on their way with the utmost freedom and dignity, bumping into everyone who meets them and who does not step aside. And so all things everywhere are just bursting with the spirit of liberty.”

[563d] “It is my own dream you are telling me,” he said; “for it often happens to me when I go to the country.”

“And do you note that the sum total of all these items when footed up is that they render the souls of the citizens so sensitive that they chafe at the slightest suggestion of servitude and will not endure it? For you are aware that they finally pay no heed even to the laws written or unwritten, [563e] so that forsooth they may have no master anywhere over them.”

“I know it very well,” said he.

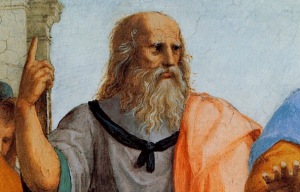

—Plato, Politeia (VIII, 562a-563e)

Reblogged this on Rise of The West.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on ElderofZyklon's Blog!.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Notes Of Man.

LikeLike